My specialty is helping startups navigate transformative change on the path from $10M to $100M in ARR. Over the course of this quarter, I’m exploring a question that’s been bugging me for years: Why aren’t we hiring leaders based on their ability to build teams of lieutenants?

We’ve all seen this story play out at some point in our careers:

A new CFO comes in and suddenly the company is choking in process.

A new CTO starts pushing out your former top performers.

A new CRO spends the next 12 months replacing everyone in their org.

A new CHRO joins in and nobody’s job feels safe anymore.

A new CMO builds a fiefdom yet seemingly accomplishes nothing.

It’s easy to chalk it all up to bad hires, bad intentions, or general incompetence. But the reality is more nuanced.

As startups scale up – the game changes.

There’s more at stake; there’s real equity value to lose. The payday from an IPO or M&A becomes material to not just the founders, but to many Directors and above. Your valuation accounts for the majority of a VC’s return – and they build their own reputation by promoting the company to their LPs as they raise the next fund.

In their own way, each of these leaders is preparing the company for its next phase of growth and dialing down the corresponding tolerance for risk — yet failing to recognize the amount of culture change this creates.

The CFO choking the company in process – is actually making sure the company is set up to have predictable revenue and earnings growth when it IPOs.

The CHRO that is creating fear – is simply raising the bar not just for hiring but for people managers, org design, and quality of leadership.

The CPO who pushes out your top performers – is prioritizing paying back technical debt, over launching shiny features shoddily built.

The CRO replacing their entire team – is focused on consistency and raising the average, over occasional moments of brilliance and reliance on a few outsized wins.

The CMO seemingly accomplishing nothing – is, in reality, investing in creating a long-term enduring brand that’s attractive not just for prospects but for public company investors as well.

So here’s the hard truth: either the startup will succeed and the culture will change to support growth at scale. Or the startup will fail – and then the culture won’t matter anymore.

If you don’t want to change your culture – someone else will do it for you.

If you want to de-risk this journey, it is vitally important that an insider, not a new hire, is the catalyst and “exec sponsor” for culture change. The job requires a thorough understanding of the fault lines in the org that can only be built over 18+ months.

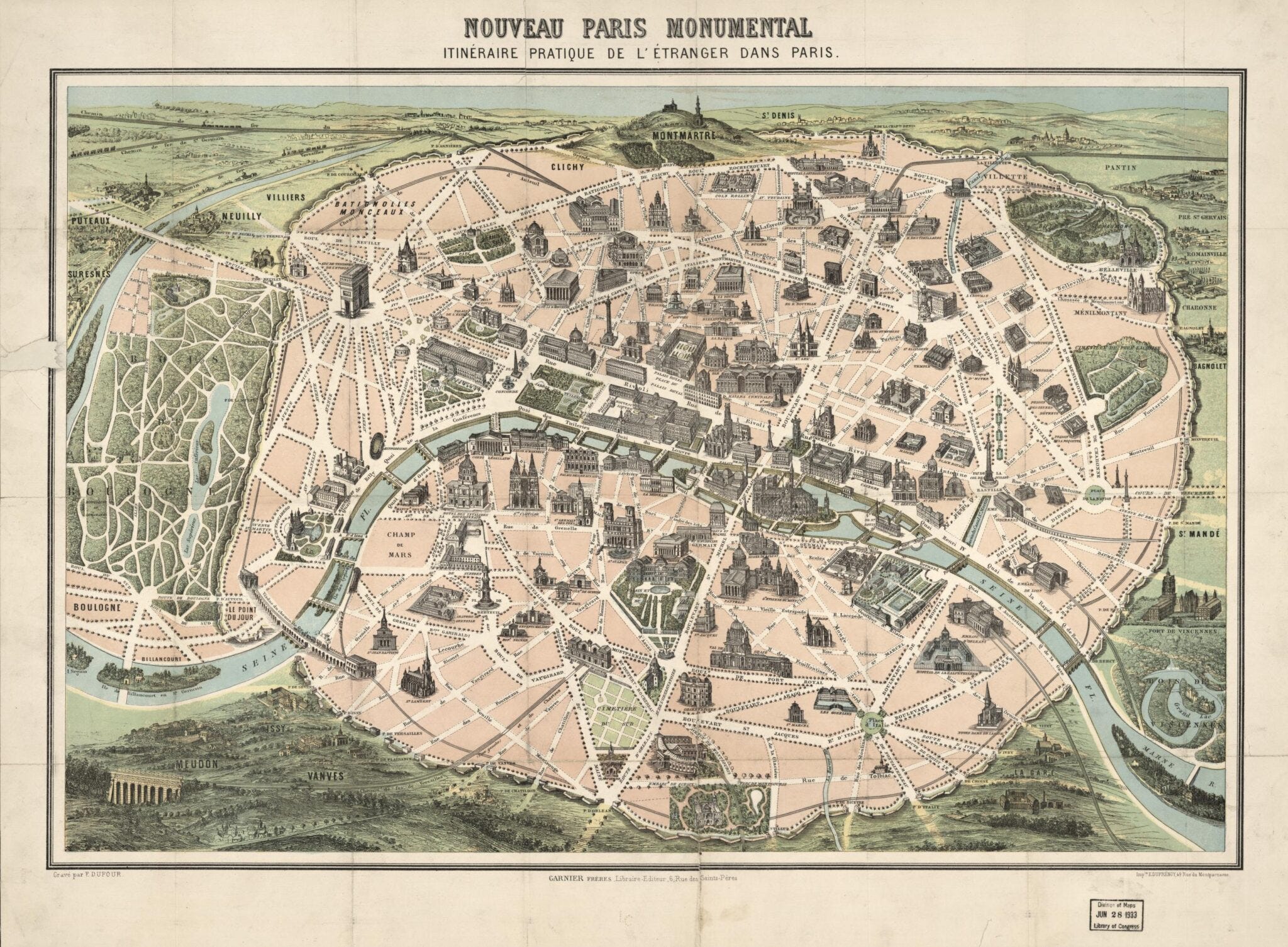

Today’s cover image is an 1878 map of Paris, showing the results of the massive rebuilding program of Baron Haussmann under Napoleon III. Most of medieval Paris was demolished (which is why Le Marais feels so different from the rest of the city today), grand boulevards were opened up, graveyards were relocated (creating the catacombs), and new cultural magnets were built. Modern Paris emerged as a result.

If you want to be that exec sponsor for culture change, three things are part of your unofficial job description:

[1] Manage the pace of change.

If you move too fast, old talent with institutional knowledge will walk out the door. If you move too slowly, the new talent you bring in will start wondering if you really intend to embrace the change you sold them on. Your job is to get it just right — let old team members depart gracefully or adjust to the new norms; keep your new lieutenants from moving too fast and tripping over themselves; and avoid impacting your customers’ experience.

By default, you need to move quickly – then slow down in some areas based on expected business impact.

How do you know you’re moving too fast? Not based on how loudly the most disgruntled employees are complaining but based on the impact on the business result. This means that before you embark on culture change, your leading indicators and revenue forecast need to be robust and pressure-tested over time.

[2] Build a cross-company network of change agents.

You need to start by building out a layer of high-performers within your own team. Before you go broad, adapt and iterate on the culture you want to build among that group. Then, just as they are ready to move up in their career ladders, facilitate cross-functional moves into key roles for them. This will not only plant a new way of doing things within other teams but also create new, informal ties across teams that were otherwise siloed.

While some functions are more amenable to this than others (e.g., BizOps teams that act as talent feeders), some of the most impactful moves that I have seen were from Sales to Product Marketing, from Ops to Marketing, from Finance to RevOps, from Marketing to HR. To learn more about hiring talent that can do this, read my previous post: Recruiting for Organizational Resilience.

[3] Protect the business result above all else.

You can’t afford for the company to miss a revenue target during this critical time – especially if the company has been hitting its targets so far. The moment it does, the change you’ve so carefully facilitated will be blamed: “Well, if we’d retained X employee, we’d have closed that deal” or “We wouldn’t have f’ed Y up if Z was still looking after it.” The old guard will be tempted to assign blame, the new team will lose their shininess, and everyone’s leash (from CEO on down) and tolerance for risk will get shorter.

This means that, regardless of what your actual scope is, you need to ensure that not only are you hitting your own goals – but the entire company is hitting the board-level targets.

It is no coincidence that these three skills – managing the pace of change, elevating the next generation of leaders, and enabling the entire company to hit its goals – often make the difference between a functional leader topping out as an SVP and a cross-functional leader accelerating their trajectory as part of the C-Suite.

Naturally, this takes time. You need to build out your own team and have confidence it’ll continue to perform semi-autonomously while you focus on high-visibility change management. You also need to understand the fault lines in the organization, including identifying not only high-visibility roles critical to future growth but also the quiet leaders who keep the company humming without much fanfare. For more on managing the timing read 18 months before $50M in ARR.

Hard conversations will be necessary along the way. You may need to layer a former trusted lieutenant, replace a well-respected leader, or fire an employee who has been there for years.

The worst thing you can do is to avoid these tough conversations and decisions. The second worst thing you can do is to make them before you build up sufficient momentum behind the wave of changes.

This doesn’t mean waiting until it’s a foregone conclusion, and everyone lets out a sigh of relief when person X finally leaves. Instead, it means building momentum to the point where most (not all) people will say: I may disagree with the decision, but I understand why it was necessary.

To build momentum and be the exec sponsor for change, you need to project excellence far outside the bounds of your own function.

Good CMOs know how to balance investing in long-term brand creation and achieving short-term pipeline goals that keep sales, finance, and founders happy. Great CMOs understand that the wider employee base, not just prospects, is a key audience consuming your brand marketing. Good CFOs are in full command of the company’s financials, managing against multiple scenarios and carefully balancing growth investment and risk. Great CFOs understand that their job is not to hold others accountable with sticks and carrots but to enable everyone around them to hit goals. Good CROs know their job security is dependent on their ability to consistently hit a number. Great CROs leverage the scope and scale of their team – including Sales Engineering, RevOps, and Customer Success – to partner with the rest of the organization and channel feedback into the product roadmap and strategic planning decisions. Good Founders know the buck stops with them and make the tough decisions. Great Founders build teams that are accountable to each other and rarely need to escalate to the founder.

Over the next few weeks, I’ll be diving into individual C-Suite roles to unpack what makes that leadership job uniquely hard, why your lieutenants make all the difference, and how to avoid topping out as a single-function leader.

Do these challenges sound familiar?

If you’re looking to unlock the next phase of growth for your team and company, I offer project-based strategy & advisory work for Founders & CxOs. Together, we’ll work through your strategic options, close your go-to-market gaps, and elevate your team.

Alternatively, consider sponsoring a 1-on-1 coaching engagement with me for your high-potential middle manager. Together, the three of us will work through a structured program that’s proven to remove their ceiling and enable you, as their leader, to do your best work.